1 - Programming under GNUstep#

This article was originally published in Linux Magazine France n°49, April 2003

Authors: Nicolas Roard and Fabien Vallon

Translation: Gerold Rupprecht and Nicolas Roard

This section is currently not under an open-source license.

Cleaned up by Ethan C

This article needs to be cleaned up. Converted from https://web.archive.org/web/20190926105521if_/http://www.roard.com/docs/lmf2.article/en.html

[X] Fix code blocks

[ ] Fix spelling

[ ] Turn symbol and file names into

code font[ ] Download pictures into this directory

[ ] Add captions to pictures

Following the GNUstep project presentation in issue number 47, we will start a small application project that we will evolve and extend throughout the year.

Application description#

This month we are going to start with something simple. The objective of the program that we are going to make is to note and manage tasks to be done; the application name will be “Todo.app”.

The interface for the time being will be very simple, displaying the task list in the upper part and the task contents (description, date, etc.) in the lower part. It will of course be possible to add or delete a task, and even to save them all into a file.

This allows us to present the RAD (Rapid Application Development)[1] tool supplied with GNUstep, Gorm, and to introduce some of the currently used Design Patterns[2] in a GNUstep application.

You will notice over the course of these articles that the GNUstep framework itself makes heavy use of a number of known patterns.

Model-View-Controller#

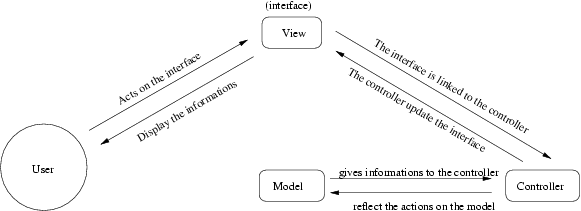

Lets start with the very classic Model-View-Controller, which we can see in the following figure.

This pattern consists of separating the application into three parts.

The model represents the business logic, namely the part of independent code from the graphic presentation or the interaction with the user.

The view is responsible for representing the model to the user.

The controller creates the link between the model and the view.

This separation into three parts allows a cleaner conception: nothing stops you from using your model elsewhere (in a GNUstep web application for example), or to completely change your view while being sure to not affect the rest of your application.

In our case the graphic interface with which the user will interact with will be the View part. This graphic interface will be created with Gorm.

Figure 1 - The Model-View-Controller Pattern#

Delegation#

This pattern consists of sending certain work to a helper object called the delegate. The classic approach in object programming to improve or specialise an object is to sub-class it. The delegate consists not of modifying the object, but simply asking certain information or certain actions from the helper object. This pattern often helps to eliminate the necessity for a sub-class and thus simplifies the program.

To return to the analogy given by Aaron Hillegass[3], the sub-class falls back on the “Robocop” approach: to improve the policeman, we employ dozens of surgeons, and you must know perfectly how the human body functions. It is a powerful tool, but can be complex to manipulate.

Delegation returns to the “Knight Rider” approach: to improve Michael, we simply use a tool created for him, the car Kitt, which has all the indespensible gadgets required for the difficult (!) life of a policeman on roller skates.

For example, when a NSTableView widget (which displays a table or a list) needs to display itself, instead of subclassing it so that it responds to our needs, we can supply it with a delegate object.

When the NSTableView wants to draw itself, it will simply ask its delegate something like “How many lines do I have?” or “What should be displayed in the first column on the third line?”.

Implementation#

Lets see if we can apply these patterns to our program.

The model#

Our model will be the task to be done, that is an object containing all related information for a given task. We will call this object class Todo. A Todo object contains for the moment three data members: a string of characters containing the task description, a character string containing an eventually more detailed note, and finally an integer containing the task progression indicator (maximum 100).

Each object could eventually contain subtasks, that is, other objects of the Todo class.

To simplify things we will allow having several application level tasks; we will thus simply have a table containing one or more Todo objects at the controller level.

Here is the interface of our model (placed in a Todo.h file):

#ifndef __TODO_H__

#define __TODO_H__

#include <Foundation/Foundation.h>

@interface Todo : NSObject

{

NSString *_note;

NSString *_description;

int _progress;

NSMutableArray *_children;

id _parent;

}

// Constructor

-(id) initWithDescription: (NSString*) description andNote: (NSString*) note;

// modifiers

-(void) setDescription: (NSString *) description;

-(void) setNote: (NSString *) note;

-(void) setProgress: (int) progress;

-(void) setChildren: (id) children;

-(void) addChild: (id) child;

-(void) setParent: (id) parent;

-(void) removeChild: (id) child;

// accessors

-(NSString *) desc;

-(NSString *) note;

-(int) progress;

-(id) parent;

-(NSArray*) children;

@end

#endif

Each Todo object could eventually contain subtasks (stored in the _children table); we can access the parent task if it exists by sending the parent message:

id ParentTask = [myTask parent];

Here is the code for our model (placed in the Todo.m file) :

#include "Todo.h"

@implementation Todo

/* Constructors */

-(id) init {

self = [super init];

_note = [[NSString alloc] init];

_description = [[NSString alloc] init];

_children = [[NSMutableArray alloc] init];

_parent = nil;

_progress = 0;

return self;

}

-(id) initWithDescription: (NSString*) description andNote: (NSString*) note {

self = [super init];

_description = [[NSString alloc] initWithString: description];

_note = [[NSString alloc] initWithString: note];

_children = [[NSMutableArray alloc] init];

_parent = nil;

_progress = 0;

return self;

}

/* Destructor */

-(void) dealloc {

RELEASE(_children);

RELEASE(_note);

RELEASE(_description);

[super dealloc];

}

/* Accessors */

-(NSString *) desc { return _description; }

-(NSString *) note { return _note; }

-(int) progress; { return _progress; }

-(NSArray *) children { return _children; }

-(id) parent { return _parent; }

/* Modifiers */

-(void) setDescription : (NSString *) description {

[_description release];

_description = [[NSString alloc] initWithString: description];

}

-(void) setNote : (NSString *) note {

[_note release];

_note = [[NSString alloc] initWithString: note];

}

-(void) setProgress: (int) progress {

if ((progress >= 0) && (progress < 100))

{

_progress = progress;

}

}

-(void) addChild: (id) child {

[_children addObject: child];

}

-(void) setParent: (id) parent {

ASSIGN (_parent, parent);

}

-(void) setChildren: (id) children {

ASSIGN (_children, children);

}

-(void) removeChild: (id) child {

[_children removeObject: child];

}

@end

The View#

Even it it is absolutely possible to manually develop the interface, a RAD tool exists as part of the GNUstep development platform, a clone of the OPENSTEP/MacOSX Interface Builder named Gorm[4].

Even if the version number is only 0.2.6, Gorm is already very usable (and used) for the development of graphical interfaces.

Gorm is part of the GNUstep project and is thus in the CVS.

Gorm Installation#

cvs -z3 -d:pserver:anoncvs@subversions.gnu.org:2401/cvsroot/gnustep co Gorm

cd Gorm

cd GormLib; make; su -c "make install"; cd ..

make

make install

You can download the tgz packages from the GNUstep project website (http://www.gnustep.org).

Creating the graphic interfaces#

“For the novice or occasional user, the interface must be simple and easy to learn and remember. It should not need to be relearned after a long absence from the computer.”

(NeXT Interface Guide)

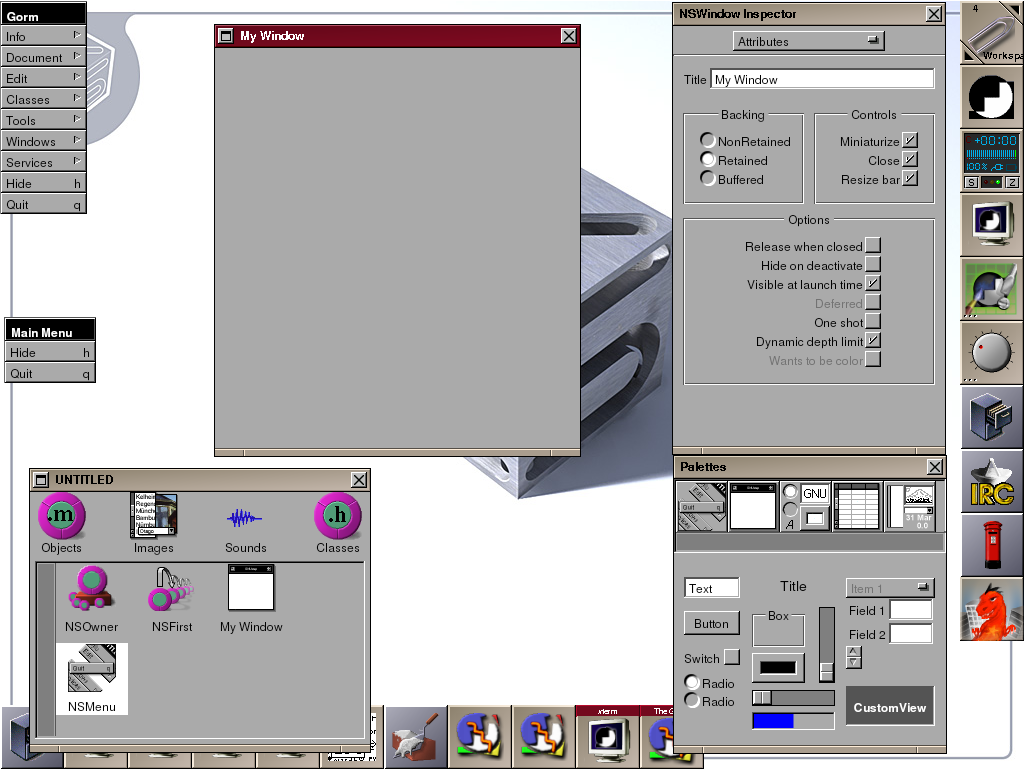

Launch Gorm:

openapp Gorm.app

Create a new application: Document → New Application.

Figure 2 - Creating an application#

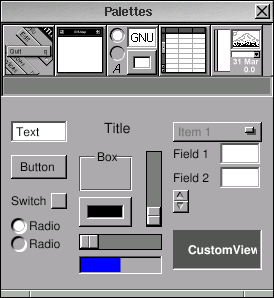

In the “Tools” menu click on “Palettes” and “Inspector”.

The palettes window contains various needed objects that make up an interface (windows, buttons, textfields…).

Figure 3 - the Palettes window#

In this window (see figure), by clicking on the different sections, we have in order from left to right:

The Menus and menu items (for the application menu).

The windows and Panels

The controls (Buttons, Textfields, Sliders…)

The containers (TreeView and TextView)

The Inspector window represents the different object views that we can manipulate; Figure 2 shows for example in the attribute inspector the window attributes (NSWindow) of our application.

The inspectors are often found in GNUstep, OpenStep, and Cocoa applications; they allow, for example, to display additional details on a document when needed, instead of uselessly encumbering the screen with this information when it is not necessary.

In Gorm’s inspector, we have the following views (by manipulating the drop down list):

Attributes: allows defining the selected widget attributes

Connection: allows defining the connections between different objects (graphical or not)

Size: The initial size and resizing characteristics of an object

Help: The help.

The interface of our Todo.app program will be made up of an NSOutlineView widget, displaying a task list in a tree like manner (because we will eventually have sub tasks), accompanied with several buttons (add a task (“+”), add a sub task (“<”), delete a task (“-“)).

For the moment, the lower part of the Todo.app window will directly display the selected task contents. It will contain two NSTextFields (Description and Note) and a NSProgressView displaying the task progression. We will also add an “Update” button which will be used to update a task that we have modified.

We will change this next month to have an inspector (a separate window) on a task instead of including everything in the main window.

Go in the “Contents” section of the Palettes panel and put a NSOutlineView widget. When you place the objects in your window, you will see “magnets” lines (the red lines) which permits you to position correctly your objects according to the guideline (see figure).

Double-click on the NSOutlineView, and a second time on the first column’s title (for editing it), and write “Description”. In the inspector, set the identifier DESCRIPTIONTAG to this column. Do the same thing for the second column, with “Status” as title and STATUSTAG as identifier.

After that, put a NSTextField (which will contain the description of a Todo), a NSTextView (which will contain the eventual details of this Todo), and an horizontal NSSlider for the progression.

Add the corresponding labels on the widgets’ sides. For editing a label, double-click simply on it and enter the text (“Description”, “Note”, “Progression”). Align the labels text to the right.

Let us pass to the menu; we add the “infos” item.

Be careful : the order of the items is important; for example, putting the Preferences or the Information Panel in other place than the Infos submenu (which should be the first menu item) should be considered as an ergonomy fault (at least, a non-respect of the *step guideline).

The next figure shows the result that you should have for the graphical interface.

Connecting the View and the Controller#

We have now a View (our graphical interface), and a model (our Todo class). We miss a controller in order to make everything works.

What will be the controller actions ? We want to :

view a task

add a task:

addTodo:add a sub-task:

addSubTodo:remove a task:

removeTodo:update a task:

updateTodo

Our controller will stock the task list in an array (NSMutableArray), the different actions will be directly linked to the buttons of our GUI. A click on a line in our task list will update the fields Note, Description, in order to view the contents of the selected task.

The controller will then have access to the fields Note and Description, and to the NSOutlineView listing the tasks, in order to update their state. The controller will then have “pointers” to theses widgets; thoses types of pointers are called “outlet” in the GNUstep terminology.

Let us create our controller. Under Gorm, in the Document panel, go in the Class Manager (following figure). We will subclass the NSObject class. Click on NSObject for selecting it if that’s not done.

Under the “Classes” menu in Gorm (I advice you to detach it and put it near the Document panel), select “Create Subclass…”. A new class is created, called NewClass. Double-click on it to change its name in TodoController, then press enter to validate the name’s modification.

Click on the gray circle in the “Outlet” column (the one similar to an electric connector), and add an Outlet (Classes->Add Outlet/Action). Rename the outlet in “descriptionText”. Add then successively the outlets “noteTextView” and “todolistView”.

Deselect the class and click on the second gray point of TodoController representing the Actions, and add (again with Classes->Add Outlet/Action) the addTodo:, addSubTodo:, removeTodo: and updateTodo: actions.

Our controller is now ready to be used. Reselect the TodoController class in the Class Manager and click on the menu item Classes->instantiate. An instance of the TodoController class is now created in the Object section of the Document panel.

It remains to connect our objects to this instance of the TodoController class.

Click on the TodoController instance while keeping pressed the control key < Ctrl > . The icon  (as Source) appears, we drag the mouse until the NSOutlineView widget used to list our tasks. The icon

(as Source) appears, we drag the mouse until the NSOutlineView widget used to list our tasks. The icon  (as Target) appears, we hold off the mouse. In the inspector, click on the “todolistView” outlet shown, then on “Connect”. The “todolistView” outlet of our controller is now connected with the NSOutlineView widget.

(as Target) appears, we hold off the mouse. In the inspector, click on the “todolistView” outlet shown, then on “Connect”. The “todolistView” outlet of our controller is now connected with the NSOutlineView widget.

We do the same to connect the remaining outlets (Note and Description fields).

We do the inverse manipulation (press the control key, etc.), from the buttons (“+”,”<”,”-” and “Update”) of our interface to the icon of the TodoController instance, in order to connect the Actions. In the inspector, click on “target” then choose the controller actions corresponding to the buttons.

Our controller is now connected with the actions and outlets which it needs.

Do the same manipulation between the outline view (our task list) and the controller, with the outline view as source and the controller as target. In the inspector, select the “dataSource” outlet of the outline view and click on “Connect”. Redo the same thing but this time connect the “delegate” outlet of the outline view to the controller. Thus, the outline view will ask the controller for the informations needed for its display.

Save the entire thing (Document->Save As…) under the name Todo.gorm .

Code of the Controller#

We could finish our controller : in the Document panel, turn over in Class Manager, and select TodoController. Then click in the “Classes” menu in Gorm and select the item “Create Class Files”. Thus the skeleton of our controller will be automatically created by Gorm. We will add in the controller an array to contain the Todo list, which will call todoArray.

For the moment, our controller is very simple :

@interface TodoController : NSObject

{

id descriptionText;

id noteTextView;

id todolistView;

NSMutableArray *todoArray;

}

- (void) addTodo: (id)sender;

- (void) addSubTodo: (id)sender;

- (void) removeTodo: (id)sender;

- (void) updateTodo: (id)sender;

@end

We will now add the “Data Source” methods used by the outline view for its display :

- (id) outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView child: (int) index ofItem: (id) item;

- (int)outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView numberOfChildrenOfItem: (id) item;

- (BOOL)outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView isItemExpandable: (id) item;

- (id)outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView objectValueForTableColumn: (NSTableColumn *) tableColumn byItem: (id) item;

If our TodoController object responds to this messages, the outline view will use them for its display. The methods are quite simple in fact :

The first must return the child placed at the index position of the item object.

The second must return the number of children that an item object will contains.

The third method must return YES (true) if the object passed in parameters item contains – or not – children.

The fourth method must return the cell value for a column, for the object given in parameter (so, for a line of the outline view). We could use “tags” (like thoses we entered earlier in Gorm) to do the selection

We could note that the NSOutlineView widget inherit the NSTableView widget; its behavior is a bit more complex (as it uses a tree structure), but is based on the same principles. In fact, the original version of this article used a NSTableView, and didn’t used a tree structure for the Todo, but as we were shifted from one month, we profited to add some things ;-)

We also add to our controller a delegate function of the outline view, which will be called when the user will select an item (a Todo); so we will know when to update the Note and Description fields and the Progression according to the selected Todo.

The interface of our controller (which will be saved in a TodoController.h file) will then be :

#ifndef __TODOCONTROLLER_H__

#define __TODOCONTROLLER_H__

#include <AppKit/AppKit.h>

@interface TodoController : NSObject

{

id descriptionText;

id noteTextView;

id todolistView;

id sliderView;

id progressView;

NSMutableArray *todoArray;

}

// Actions

- (void) addTodo: (id)sender;

- (void) addSubTodo: (id)sender;

- (void) removeTodo: (id)sender;

- (void) updateTodo: (id)sender;

- (void) setProgress: (id)sender;

// NSOutlineView Data Source

- (id) outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView child: (int) index ofItem: (id) item;

- (int)outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView numberOfChildrenOfItem: (id) item;

- (BOOL)outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView isItemExpandable: (id) item;

- (id)outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView objectValueForTableColumn: (NSTableColumn *) tableColumn byItem: (id) item;

// NSOutlineView delegate method

- (BOOL)outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView shouldSelectItem: (id) item;

@end

#endif

We just need to add the corresponding code (in a TodoController.m file) :

#include "Todo.h"

#include "TodoController.h"

@implementation TodoController

-(id) init {

self = [super init];

todoArray=[[NSMutableArray alloc] init];

return self;

}

-(void) dealloc {

RELEASE(todoArray);

[super dealloc];

}

// Actions

-(void) addTodo:(id) sender {

Todo *aTodo = [[Todo alloc] initWithDescription: [descriptionText stringValue]

andNote: [noteTextView string]];

[todoArray addObject: aTodo];

[aTodo release];

[todolistView reloadData];

}

-(void) addSubTodo:(id) sender {

int row = [todolistView selectedRow];

if (row != -1)

{

id item = [todolistView itemAtRow: row];

Todo *aTodo = [[Todo alloc] initWithDescription: [descriptionText stringValue]

andNote: [noteTextView string]];

[aTodo setParent: item];

[item addChild: aTodo];

[aTodo release];

[todolistView reloadData];

}

}

-(void) removeTodo:(id) sender {

int selectedRow = [todolistView selectedRow];

if (selectedRow != -1)

{

id item = [todolistView itemAtRow: selectedRow];

id parent = [item parent];

if (parent != nil)

{

[parent removeChild: item];

}

else

{

[todoArray removeObject: item];

}

[todolistView reloadData];

}

}

-(void) updateTodo:(id) sender {

int selectedRow = [todolistView selectedRow];

if (selectedRow != -1)

{

Todo* todo = [todolistView itemAtRow: selectedRow];

[todo setDescription: [descriptionText stringValue]];

[todo setNote: [noteTextView string]];

[todo setProgress: [progressView doubleValue]];

[todolistView reloadData];

}

}

-(void) setProgress:(id) sender {

[progressView setDoubleValue: [sender intValue]];

}

/* dataSource methods of the outline view */

- (id) outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView child: (int) index ofItem: (id) item

{

if (item == nil) // racine

{

return [todoArray objectAtIndex: index];

}

return [[item children] objectAtIndex: index];

}

- (int)outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView numberOfChildrenOfItem: (id) item

{

if (item == nil) return [todoArray count];

return [[item children] count];

}

- (BOOL)outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView isItemExpandable: (id) item

{

if ([[item children] count] > 0) return YES;

return NO;

}

- (id)outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView objectValueForTableColumn: (NSTableColumn *) tableColumn byItem: (id) item

{

if ( [[tableColumn identifier] isEqualToString: @"DESCRIPTIONTAG"] )

{

if (item == nil)

return [[todoArray objectAtIndex: 0] desc];

return [item desc];

}

else if ( [[tableColumn identifier] isEqualToString: @"STATUSTAG"] )

return [NSString stringWithFormat:@"%i/100", [item progress]];

return [NSString stringWithString: @"VOID"];

}

/* delegate methods of the outline view */

- (BOOL)outlineView: (NSOutlineView *) outlineView shouldSelectItem: (id) item

{

if (item)

{

[descriptionText setStringValue: [item desc]];

[noteTextView setString: [item note]];

[progressView setDoubleValue: [item progress]];

[sliderView setIntValue: [item progress]];

return YES;

}

return NO;

}

@end

The main function of our programme#

The main of our program will simply call the NSApplication object and do some necessary initialisations :

int main(int argc, const char *argv[])

{

return NSApplicationMain(argc, argv);

}

We will save it in a main.m file.

The Makefiles#

GNUstep provides its own system of makefiles for the different environments and systems, without using (directly) the complexes autoconf/automake. The makefile file must be called GNUmakefile.

gnustep-make is based on environments variables. Here is an exemple of a GNUmakefile for a “tool” – that is, a non-graphic GNUstep application. The different scripts are located in /System/Makefiles/

include $(GNUSTEP_MAKEFILES)/common.make

TOOL_NAME= MyTool

MyTool_OBJC_FILES=main.m source.m

include $(GNUSTEP_MAKEFILES)/tool.make

Here is a small list of commonly used variables; We will prefix them with the AppName of the application :

|

list of subprojects |

AppName |

the Objective-C files |

AppName |

the C files |

AppName |

the header files |

AppName |

public header files that should be installed ( for a framework) |

AppName |

the resource files used by the program (for example images, Gorm interfaces) |

AppName |

resource files localized or translated into different languages |

AppName |

the languages supported by the app |

Here is the GNUmakefile of our Todo.app application :

include $(GNUSTEP_MAKEFILES)/common.make

APP_NAME=Todo

Todo_OBJC_FILES=main.m TodoController.m Todo.m

Todo_RESOURCE_FILES=Todo.gorm

Todo_MAIN_MODEL_FILE=Todo.gorm

include $(GNUSTEP_MAKEFILES)/application.make

Let us compile it: make

Our application is called Todo.app. You could launch it by typing openapp Todo.app .

For the moment, you could add, modify and delete tasks… but we miss a small detail : the saving and reading of Todo files !

Archiving an object#

Archiving an object consists to transform it in a binary flow, architecture-independant, which preserves the identify and the relations between the objects and their values. It permits for example to send an object on the network or to save it on disk easily. Dearchiving an object, is to do the inverse operation, recreating an object from a binary flow. GNUstep permits to do it very easily.

In order to archive/dearchive an object, it just need to implement the NSCoding protocol, i.e, to implement the messages encodeWithCoder: (for archiving an object) and initWithCoder: (for dearchiving object).

Thoses two methods received in parameter an object of NSCoder type. The abstract class NSCoder is used to represent the binary flow, and to add to it the various data members of the object we want to archive. Indeed, the object is responsible of the encoding of its data members. It’s not forced to encode all its data members (some could be considered as non-important). But it’s required to keep the same encoding/decoding order of the datas, else you will have problems (see the following source). If you want to archive an object inheriting another object which responds also to the NSCoding protocol, you must add the line :

[super encodingWithCoder: coder];

in the beginning of the encoding method encodeWithCoder and

self = [super initWithCoder: coder];

in the beginning of the deencoding method initWithCoder, so the data members of the father object will possibly be encoded if needed.

In our case, it’s not necessary, as Todo inherits directly from NSObject.

The objects of the GNUstep framework knows already how to encode or decode themselves, so it will thus be enough to use the encodeObject: method on the coder object given in parameters.

On the other hand, for C base types, you must use the methods encodeValueOfObjcType: and decodeValueOfObjCType: to whom you pass a macro @encode() which defines the type and address of the variable we want to encode.

We thus add the functions encodeWithCoder: and initWithCoder: to our Todo object :

/* Encoding of the object */

- (void) encodeWithCoder: (NSCoder*) coder {

[coder encodeObject: _description];

[coder encodeObject: _note];

[coder encodeValueOfObjCType: @encode(int) at: &_progress];

[coder encodeObject: _parent];

[coder encodeObject: _children];

}

- (id) initWithCoder: (NSCoder*) coder {

if (self = [super init])

{

[self setDescription: [coder decodeObject]];

[self setNote: [coder decodeObject]];

[coder decodeValueOfObjCType: @encode (int) at: &_progress];

[self setParent: [coder decodeObject]];

[self setChildren: [coder decodeObject]];

}

return self;

}

Here we are ! our Todo objects now knows how to encode and decode themselves. We must now add to our controller the methods for reading and saving our Todo objects.

Modification of TodoController#

We add two methods prototypes in TodoController.h :

-(void) saveFile: (id) sender;

-(void) loadFile: (id) sender;

We add the body of theses methods in TodoController.m :

-(void) saveFile: (id) sender {

int ret;

NSSavePanel* panel = [NSSavePanel savePanel];

[panel setRequiredFileType: @`Todo`];

[panel setDirectory: [[NSFileManager defaultManager] currentDirectoryPath]];

ret = [panel runModal];

if (ret == NSFileHandlingPanelOKButton)

{

[[NSArchiver archivedDataWithRootObject: todoArray] writeToFile: [panel filename] atomically: YES];

}

}

-(void) loadFile: (id) sender {

int ret;

NSOpenPanel* panel = [NSOpenPanel openPanel];

[panel setAllowsMultipleSelection: NO];

[panel setDirectory: [[NSFileManager defaultManager] currentDirectoryPath]];

ret = [panel runModalForTypes: [NSArray arrayWithObject: @`Todo`]];

if (ret == NSOKButton)

{

id file = [NSUnarchiver unarchiveObjectWithData:

[NSData dataWithContentsOfFile: [[panel filenames] objectAtIndex: 0]]];

ASSIGN (todoArray, file);

[todolistView reloadData];

}

}

Some remarks : we choosed to use it the FileType Todo, that is, the “.todo” extension, for our saved files. The interesting point here is the use of the NSArchiver and NSUnarchiver classes, to whom we simply pass the array todoArray containing our Todo objects.

Modification of the gorm file#

Now that everything functions perfectly and that our application knows how to read and save Todo files, it could be interesting to let the user do it…

Launch Gorm on our Todo.gorm file : gopen Todo.gorm. Go in the Class Manager, and reload the TodoController Class («Classes->Load Class…» then read the TodoController.h file). Now, add two items in our application menu :

Then, link the menu items “Open…” and “Save as…” to the TodoController controller, and connect them to the actions “loadFile:” and “saveFile:” now availables in the controller. Save the Gorm file, recompile the program (make), and voila !

You have now a functional Todo.app version – basic, but entirely functional. The next month we will modify the program to add an inspector… Until then, you are welcome to join the #gnustep channel on freenode irc network (irc.debian.org for example) !

Credits#

Contact the authors

Nicolas Roard, nicolas@roard.com

Fabien Vallon, fabien@tuxfamily.org

Contributors

Thanks to Vincent Ricard and Cyril Siman for reviewing this article !

Big thanks to Gerold Rupprecht for the traduction and Matt Rice for reviewing this article in english :-)

Links#

The GNUstep wiki : http://wiki.gnustep.org/

The tutorial page of the wiki : http://wiki.gnustep.org/index.php/Tutorials

A very good tutorial from Yen-Ju : http://www.people.virginia.edu/~yc2w/GNUstep/Tutorial/